journal

Labour workers are already being replaced by automation, and as we look into a future of constant technological advancement, it’s difficult to grasp the scale of automation’s effect on peoples’ everyday lives. How many times will people in the future need to reinvent themselves, and in which ways? And what moral aspects should employers start considering as we head toward an increasingly automated society?

Citing government advisers, Daily Handelsblatt recently reported that The shift to electric vehicles could cost 410,000 jobs in Germany by 2030. The car industry is an important driver of growth in Europe’s largest economy, and in 2018, employment in the industry in Germany reached 834,000, its highest since 1991. But because of accelerating plans to launch electric vehicles, under pressure from a European Union drive to further cut carbon dioxide emissions, the industry will not be sufficient to support the current level of jobs.

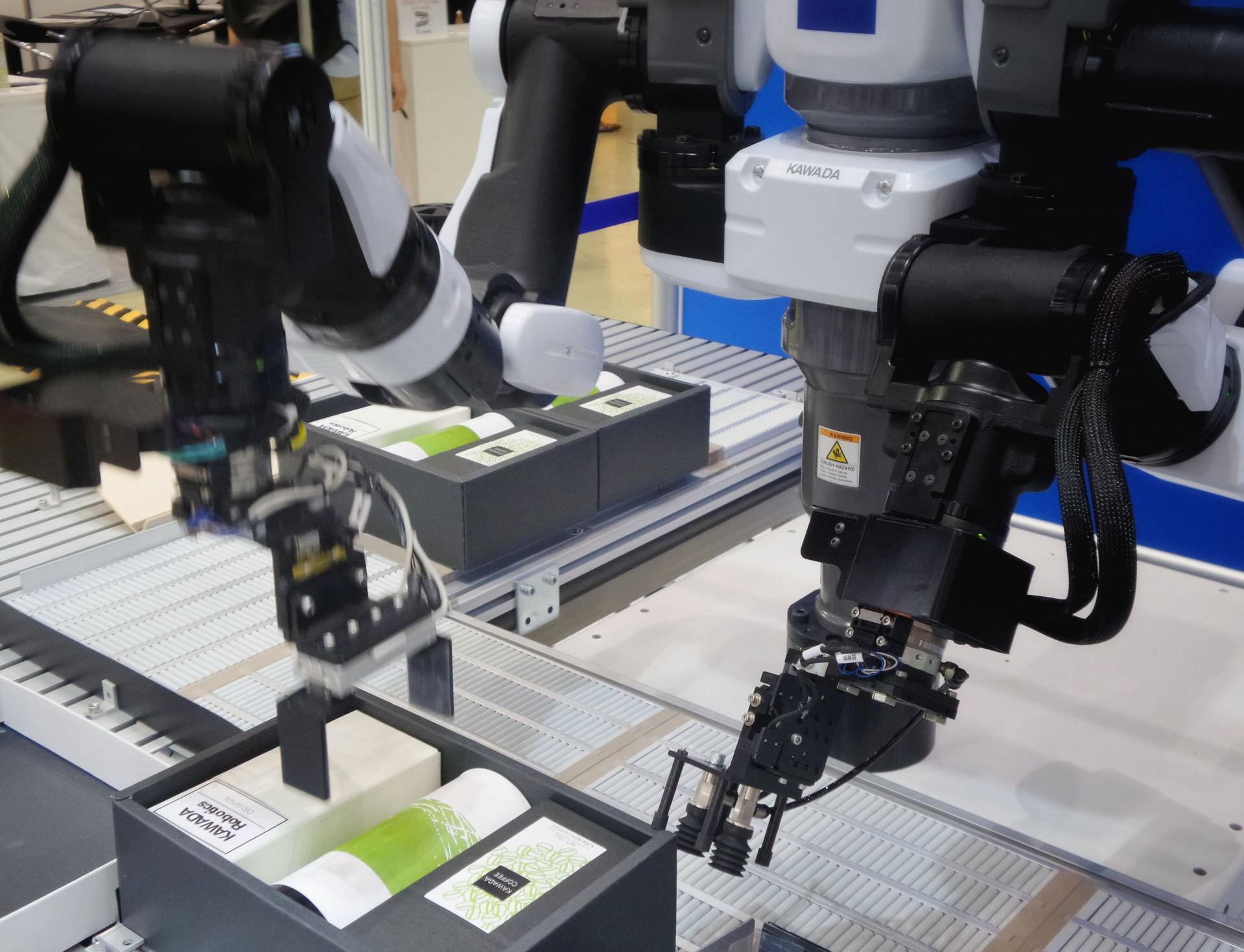

Though robots are not yet technologically advanced enough to fully replace labour forces, they’re already being used in ways that caused workers to feel that “they were forced to become machines themselves”, says an article by The Verge: Almost every aspect of management at Amazon’s warehouses is directed by software. “Every worker has a “rate,” a certain number of items they have to process per hour, and if they fail to meet it, they can be automatically fired.”

At Davos 2020 professor Yuval Noah Harari addresses this challenge. He speaks about how automation in the 21st century might make a large amount of labour workers irrelevant and create what he calls a useless class. “We aren't talking about a science fiction scenario of robots rebelling against humans, we are talking about far more primitive A.I. that is nevertheless to disrupt the global balance. What will happen to developing economies once it is cheaper to produce textiles or cars in California than in Mexico?”, he asks.“How does a fifty years old truck driver reinvent him or herself as a software engineer or yoga teacher?”

Jim Stanford, economist and director of the Centre for Future Work, and the Harold Innis Industry Professor of Economics at McMaster University recently wrote in an article for Policy Options that “work isn’t changing so fast or dramatically, and it’s humans who decide how technology is used.” He believes that we better equip ourselves to make better decisions in the future. “Automation and artificial intelligence will destroy some jobs and create others.”

But what other Jobs? In The New York Times’ Op-Eds From the Future series, journalist Brian Merchant speculates on this in his article Amazon’s First Fully Automated Factory Is Anything But: “Keeping the “human free” facility running requires the work of third-party contractors, who are often put into dangerous situations.” The fiction concludes that “automation, when deployed smartly and responsibly, can be a great labor- and timesaving technology.” But also asks whether it is morally responsible, because when opportunistic corporations use it to cut corners, it can be dangerous — perhaps even deadly.