Magazine

New ways of doing business don't materialise from thin air. They have to come from somewhere - or more often, someone.

In Part 2, we look to one visionary figure folding business together with philosophy to frame out a more generous, equitable and prosperous vision for the world.

A broader understanding of value

More than a decade after co-founding Kickstarter, Yancey Strickler has settled somewhere between a business philosopher and social critic, after recently publishing a novel-length manifesto for reforming business and rebuilding society around more equitable, fair and community-driven values.

We’re living in a rapidly changing world. Technology is evolving at an exponential rate, the climate crisis is redefining our relationship to the planet, wealth inequality is becoming more extreme and — according to the 2020 Edelman Trust Barometer survey — the general public is losing trust in most governments and companies. After many decades of relying on the mechanics of capitalism and focusing on the interests of shareholders at all costs, companies are beginning to rethink why and how they operate to adapt to this new environment and contribute to a better future.

In ‘This Could Be Our Future: A Manifesto for a More Generous World’ (2019), Kickstarter co-founder and former CEO Yancey Strickler offers an intriguing new philosophy for doing business that looks beyond profit to help build a more equitable world. He argues that our society has become so fixated on financial maximisation that we no longer even notice its influence on our decisions. “Financial maximisation imposes a monotheistic perspective on value,” he writes in the book. “Structurally, we have a problem in business. We have a problem that says the only thing a company can do is make as much money for its shareholders as possible, even though we know that companies create value in all kinds of other ways.”

From the very beginning, Kickstarter — the popular crowdfunding platform Strickler co-founded in 2009 — was built to upend a value system which put profit above and beyond all else. The platform enabled creators to fund and build a community around their ideas without going down the traditional route of finding investors who were often anxious for fast returns. In a blog post, the team stated that they “wanted to create a universe where ideas were funded not because some executive thought they seemed like a good way to make money, but because people wanted them to exist.” As of March 2020, Kickstarter has received more than $4.8 billion in pledges from 17.5 million backers to fund nearly 480,000 projects, including notable projects like the Pebble smartwatch and Peloton exercise bike which went on to file for IPO late last year.

Throughout the book, Strickler examines how businesses became obsessed with making money and challenges us to imagine an alternate society where companies integrate broader values into their mission. “The case against financial maximisation isn’t anti-money. It’s pro-money. It’s just pro-people, too,” he writes. “In service of people, money can be a very positive force. But when we live our lives serving money — by choice or because we have no choice — we severely limit our potential.”

Keenly aware that change takes time, Strickler predicts that within 30 years our society could be more fair, just and generous. To achieve this, the author is convinced that businesses need to start shifting their value systems now.

Instead of being guided by financial incentives alone, it’s important to expand the concept of value to include things like community, purpose and sustainability. “To hire quality people and earn a loyal clientele, businesses must do more than grow their bottom line,” he explains in the book. “They must find their secular mission, the unique way they can create value for their communities. Businesses that create this kind of value will survive the shock waves of new business models and other disruptive changes, and last for the long haul. Those that don’t, won’t.”

Look at what humanity has created in pursuit of financial growth. Imagine what can be accomplished if we combine our capabilities with a broader understanding of value.

In 2014, against an ocean current of startups that wanted to “move fast and break things,” Kickstarter decided to position itself differently. Announcing that it had become a certified B Corporation (See Danone, Part 1), Kickstarter joined the ranks of companies like Patagonia and Ben & Jerry’s in a sea change that officially recognises social purpose as a legitimate counterpart to — and enabler of — profit. For Strickler, turning Kickstarter into a B Corp was a way to resonate with “the next generation of people like us,” he explained on the Ezra Klein Show. “We wanted to speak to the people who felt alienated by business, but had the capacity to lead and enact change.”

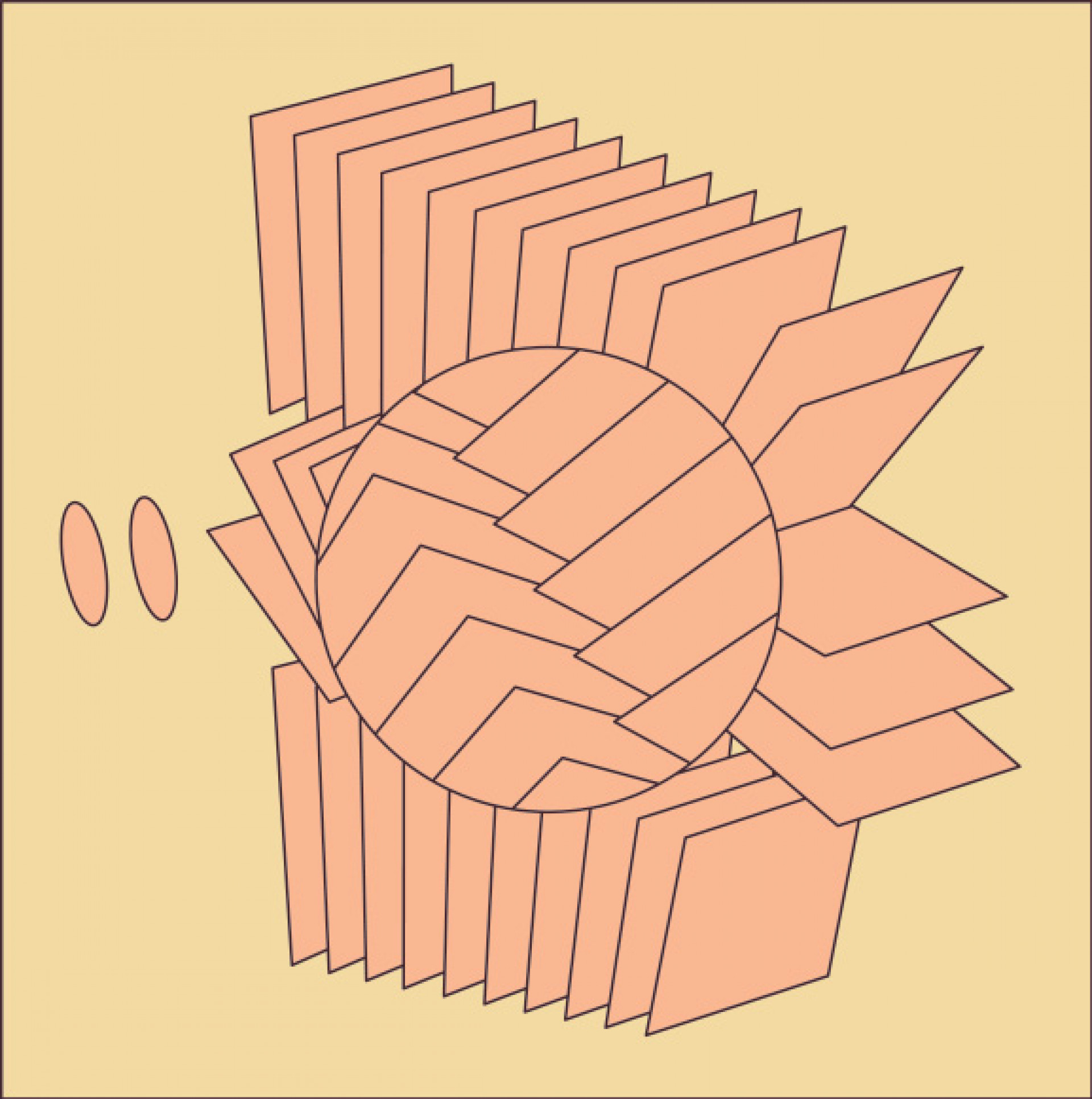

In his book, Strickler presents a new approach to decision-making called Bentoism. Based on the Japanese food box, Bentoism strives to help people and organisations look beyond the short-term emphasis of metrics like GDP and economic growth, and to take a more balanced view when making choices.

The case against financial maximization isn’t anti-money. It’s pro-money. It’s just pro-people, too.

It involves using a tool that consists of four quadrants like a Bento Box, with each compartment representing a different perspective to consider in a decision-making scenario: “Now Me” is focused on what you want most right now; “Now Us” looks at how your current behaviour will affect the people around you; “Future Me” considers the needs and wants of the future version of yourself; and “Future Us” looks ahead to what future generations, or your children, will experience. When applying this method to an organisation, Strickler explains that “Me” refers to the self-interest of the organisation and “Us” refers to all of its stakeholders, like employees, customers and the community.

As consumers sharpen their expectations of the way businesses act and the next generation of talent become more aware of a workplace’s ethics and values, it’s becoming clear that a commitment to social purpose is connected to a company’s ability to remain competitive in the long-term. Ultimately, Strickler’s philosophy is about deepening the inquiry about our spectrum of values and enabling decisions that aren’t only focused on ourselves — and our organisations — but are also meaningful to society at large moving forward. “Look at what humanity has created in pursuit of financial growth,” he writes. “Imagine what can be accomplished if we combine our capabilities with a broader understanding of value. A world where we aren’t just focused on capturing value — rather, a future where we’re focused on creating it.”