Magazine

Merging profit with purpose often requires entirely new ways of looking at familiar challenges.

In Part 3, we unfold a series of case studies where alternative platforms, approaches and business models have been put to work, profitably, both for people and the planet.

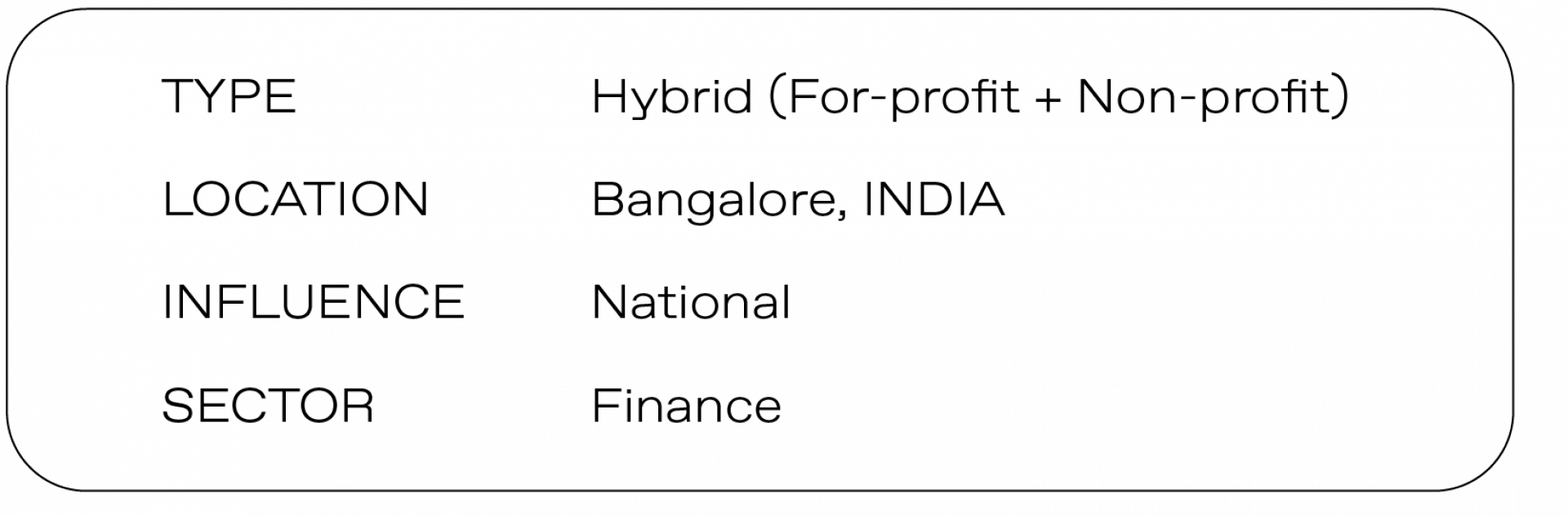

JANAKAKSHMI

A microfinance institution turned full-spectrum service provider of all financial needs of the urban poor.

There will be more than 800 million people living in India’s urban areas by 2050. Much of this growth will come from migration of the rural poor from their villages, which traditionally make up the more informal and financially under-served segments of society. The needs of these informal workers — the vegetable vendors and flower sellers, carpenters and plumbers, drivers and mechanics, domestic helpers and beauticians — differ significantly from those in formal employment and remain largely unmet by India’s service industries.

In 1999, when Swati and Ramesh Ramathanathan moved back to India from their respective banking careers abroad, they began to listen closely to the wants, wishes and challenges of all those informal workers. They needed savings accounts, access to health and life insurance, education loans, pensions and retirement plans and even financial support to grow their own micro-enterprises — all of which were inaccessible to them through formal banking systems. With all of this in mind, Janalakshmi decided to outgrow the boundaries of microfinance and become a ‘360-degree financial services company for all the needs of the urban poor’.

Their transition into a full-spectrum service provider was made possible by creating a two-tier structure. On one hand, their for-profit company raises capital from investors and is run as a full-service financial institution; while on the other, their non-profit carries out projects to deepen their understanding of the challenges of inclusion, address policy challenges and help customers in improving their pathways to prosperity.

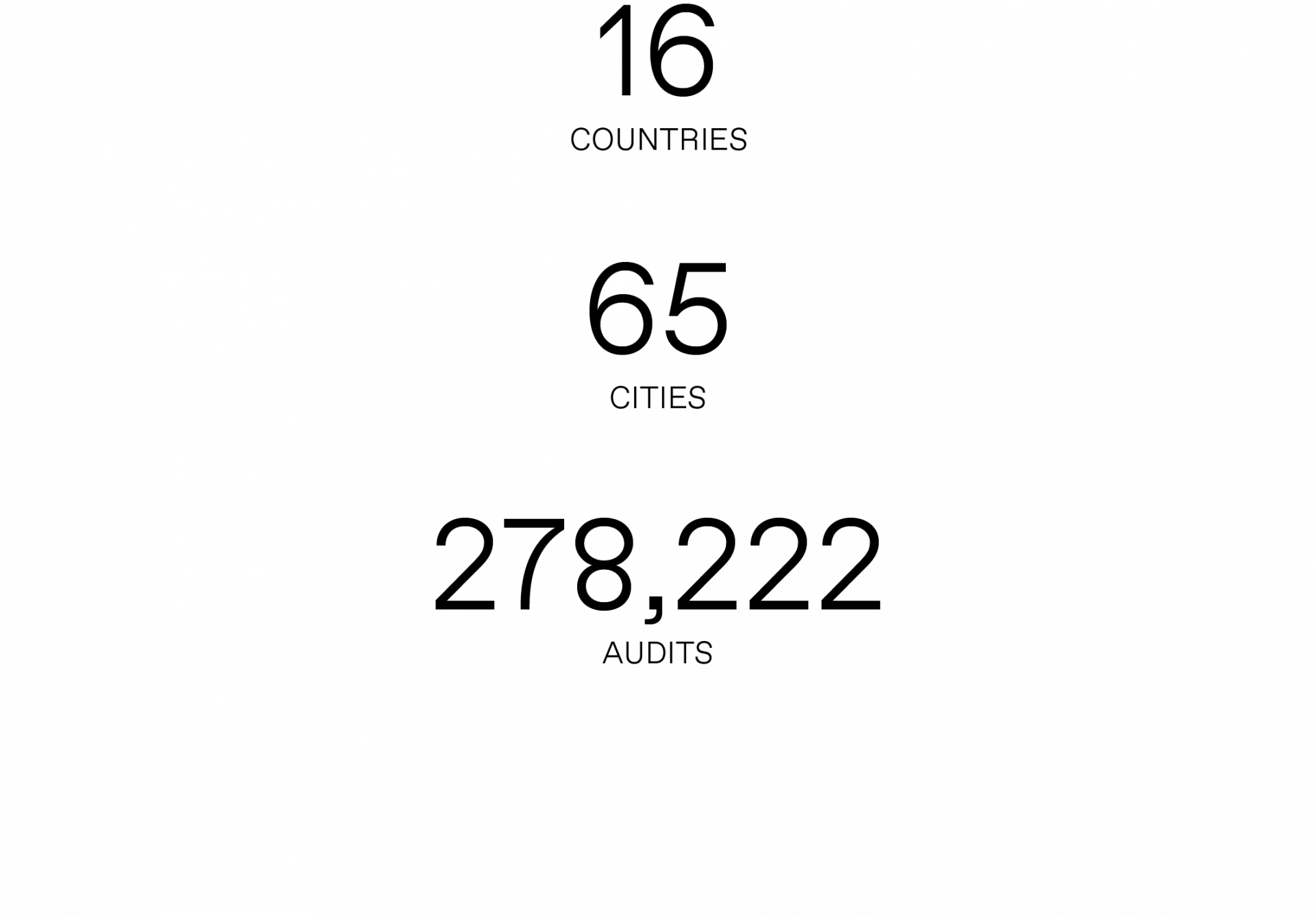

SAFETIPIN

A crowd-sourced, map-based family of apps working to make communities and cities safer for women.

According to the UN, 92% of women in New Delhi reported to have experienced some form of sexual violence in public spaces in their lifetime, and 88% experienced some form of visual or verbal harassment.More often than not, these incidents occur outside the home or the workplace — on streets and public transport and in parks, public bathrooms and water stations. The inability to safely access these spaces reduces many women’s ability to participate in everyday public life.

In 2013, Kalpana Viswanath, an expert in gender and urbanisation issues, founded Safetipin to merge new technology with a mission to address this harsh reality that so many Indian women face. Safetipin began an online participation platform for women in India to help one another identify unsafe public areas. At its core lies their safety “audits”, which assess and rate public spaces based on their relative level of safety and inclusivity, comparing factors ranging from lighting and crowd levels to the proximity of safe public transport.

The power of the app’s scalability is in its crowd-sourced data generation. Rather than relying on officials to survey areas, the audits are fed by user data which is then verified by trained auditors and other users. The initiative begins a conversation about whether a shared understanding and imagination of safer spaces can be co-created by the women that use them. In the end, data is leveraged to strategically improve the actual design and safety of the public spaces — thereby using digital space to physically build safer cities for women.

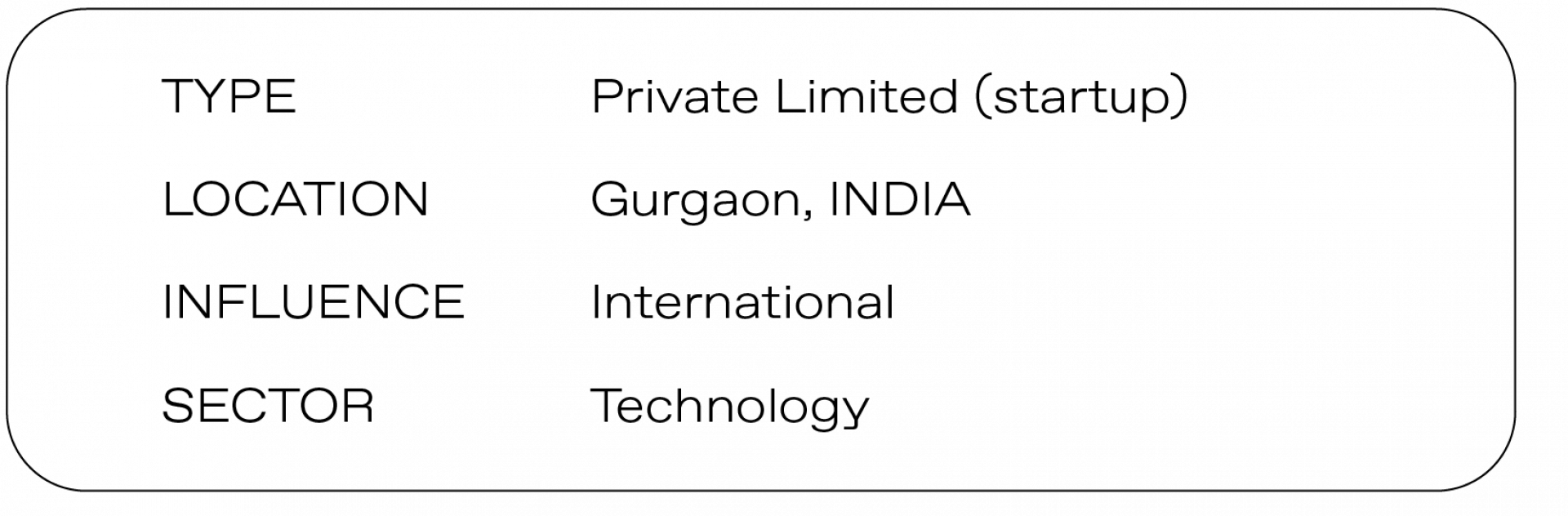

RIVIGO

A mobility and tech company building a new model of moving goods in India by changing the game of truck logistics.

Even though road transportation is an $80 billion industry in India — the single largest within national logistics — it is still highly unorganised. Nearly 95% of players own less than 30 trucks, and a single driver often takes over a week to travel between major cities, which causes logistical inefficiencies, and often requires drivers to spend more than 20 days a month away from their families.

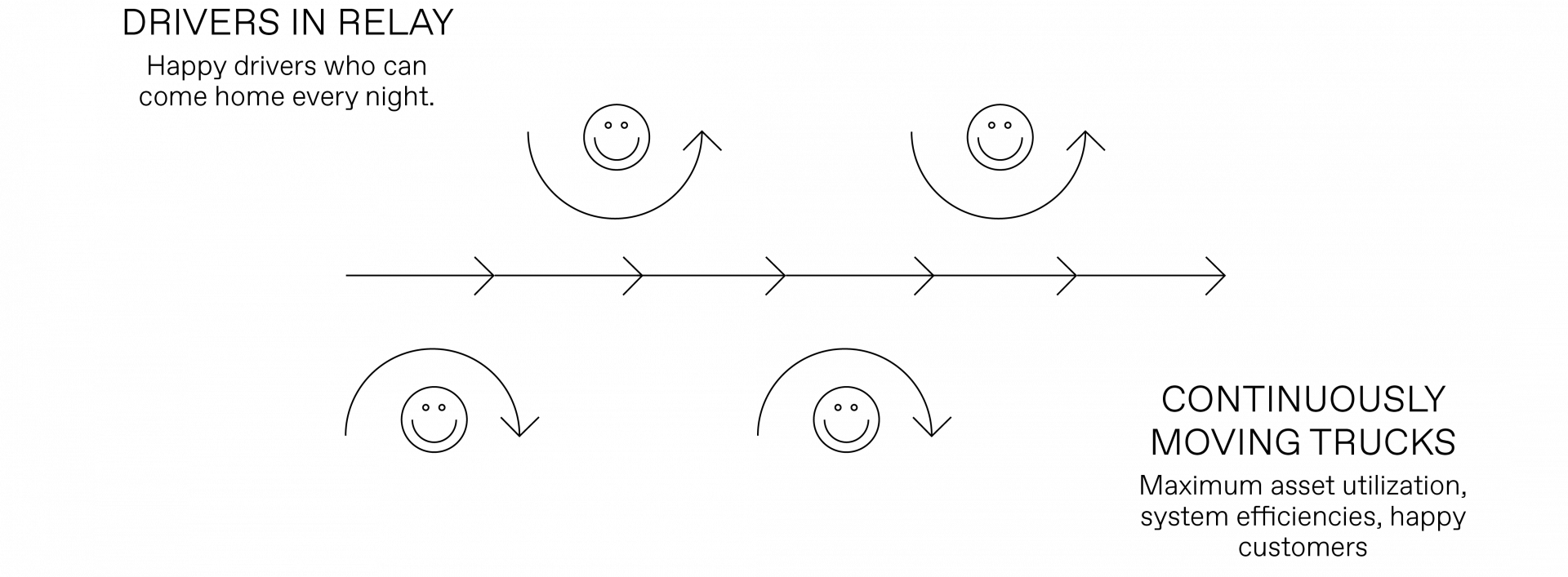

Observing these challenges, the co-founders of Rivigo set out to build a model that would create value both for paying logistical customers and the most underprivileged of all stakeholders — the truck drivers themselves. Their relay driving model sees their fleet of 3,000 trucks running almost non-stop, with drivers working across a kind of pan-Indian relay, handing over the truck to the next driver at specified pit stops along the route. After hand-over, the remaining driver would then take the wheel of another truck, making the return journey back to their home stop by the end of the day.

In order for this to be a fluid, functioning system, Rivigo leverages huge quantities and velocities of data on a daily basis. Their trucks are IoT-enabled, with the vehicle conditions being monitored in real-time, while the routing and assigning of drivers is handled by algorithms. This helps minimise breakdowns and inefficiencies, but most importantly, the model maximises vehicle usage while relieving and investing in human capital — the truck drivers. This revolutionary driving model is enabling dignified lives for truck drivers, elevating their status in society at the same time as building a billion-dollar company.

SELCO

A constellation of organisations working to electrify India by debunking common myths about rural energy access.

With a huge landmass and an average of 300 sunny days a year, India has the theoretical potential to provide clean solar power for the entire nation, dozens of times over. However, until recently, solar energy generation was nowhere near the horizon. Apart from a lack of interest from the government, there was also a common public perception that poor people cannot afford or maintain sustainable technologies, and that no social ventures in the solar energy space could be run as commercial entities.

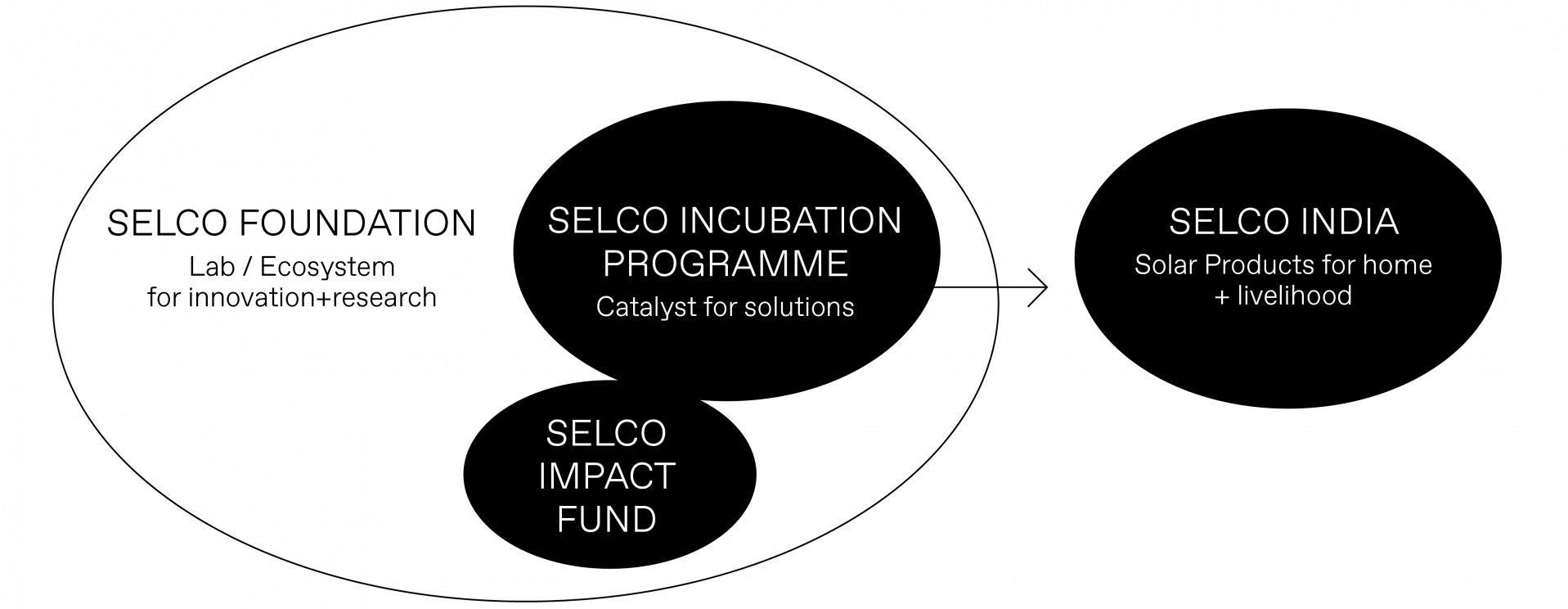

SELCO was founded in 1995 in order to disprove that misconception and use energy as a vehicle to catalyse all kinds of progress — from health to education. A key to their unconventional model was to regard the poor not as recipients, but as partners and enterprise owners. By approaching those in need of electrification as potential collaborators, they were able to build their organisation as an inclusive, sustainable solution that provides economic and social stability not only in the short-term, but also in the future.

Within a few years, they found that the biggest barrier to scaling was the absence of an ecosystem that could absorb and learn from the multitude of grass-root problems they were encountering and designing for. To overcome this, SELCO Foundation was registered in 2010 as an open-source, not-for-profit to create replicable social innovations. With their commercial business bolstered by philanthropic capital, the hybrid model of SELCO successfully bridges the gap in high-risk technological innovation and energy ecosystems, bringing into the fold under-served communities as an entirely new consumer base.

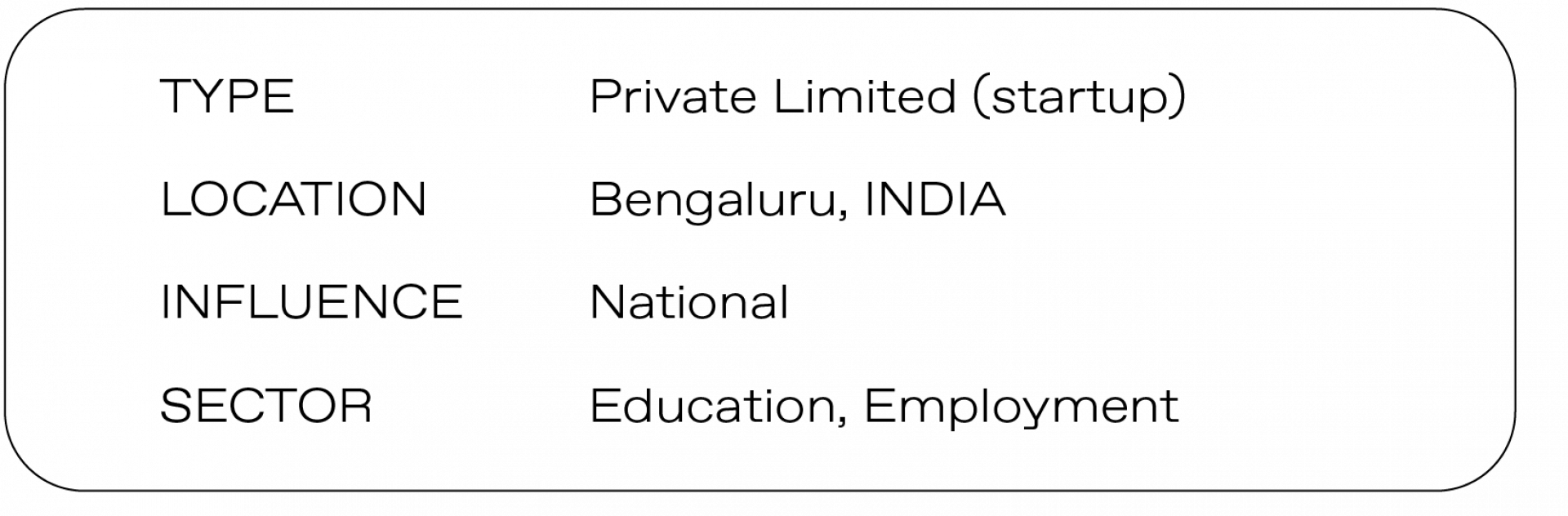

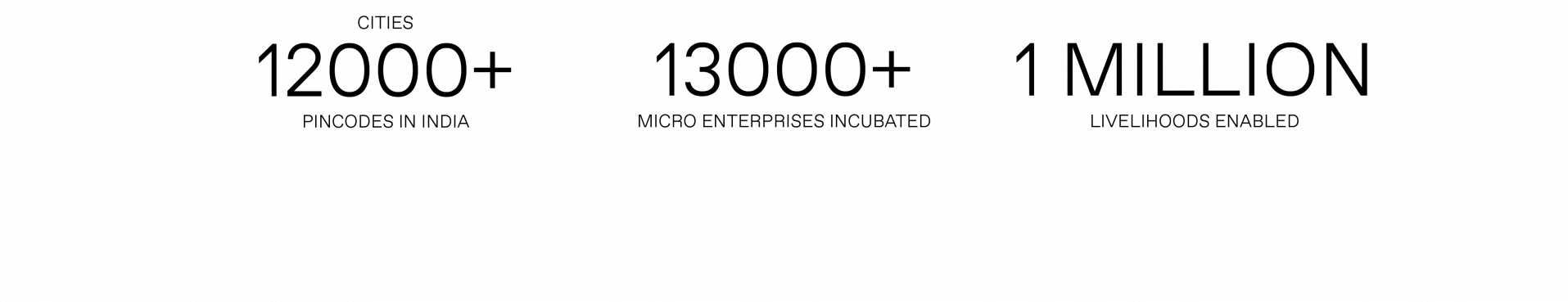

LABOURNET

A social enterprise enabling sustainable livelihoods for men, women and children throughout India’s informal value chains.

Despite high levels of economic growth during the past two decades, the informal economy in India still accounts for more than 80% of non-agricultural employment. In the informal sector, more than three-quarters of labourers and daily wage workers haven’t completed school and often operate without stable contracts, benefits or job security. Absent altogether from company payrolls, they remain especially vulnerable in the face of all manner of unexpected life circumstances.

After gaining experience at the International Labour Organisation, LabourNet’s founder Gayathri Vasudevan set out to close the gaps that kept people away from more stable and meaningful work. Beginning with an initial model of leveraging technology for linking the informal sector to jobs, soon enough LabourNet pivoted into becoming a training platform for labourers to make them more marketable and hireable for organisations.

Presently, LabourNet is uniquely poised to create social impact while delivering business value to all of the stakeholders throughout its ecosystems — for individuals (skill certification and entrepreneurship), for corporates (upskilling and access to new labour forces), for governments (partnerships on policy implementation and training centres), and for educational institutions (testing and implementing programmes). Ultimately, LabourNet’s scaled, multi-pronged approach is likely to encourage large reforms that will help empower a wider portion of India’s working population to find dignity, security and prosperity.

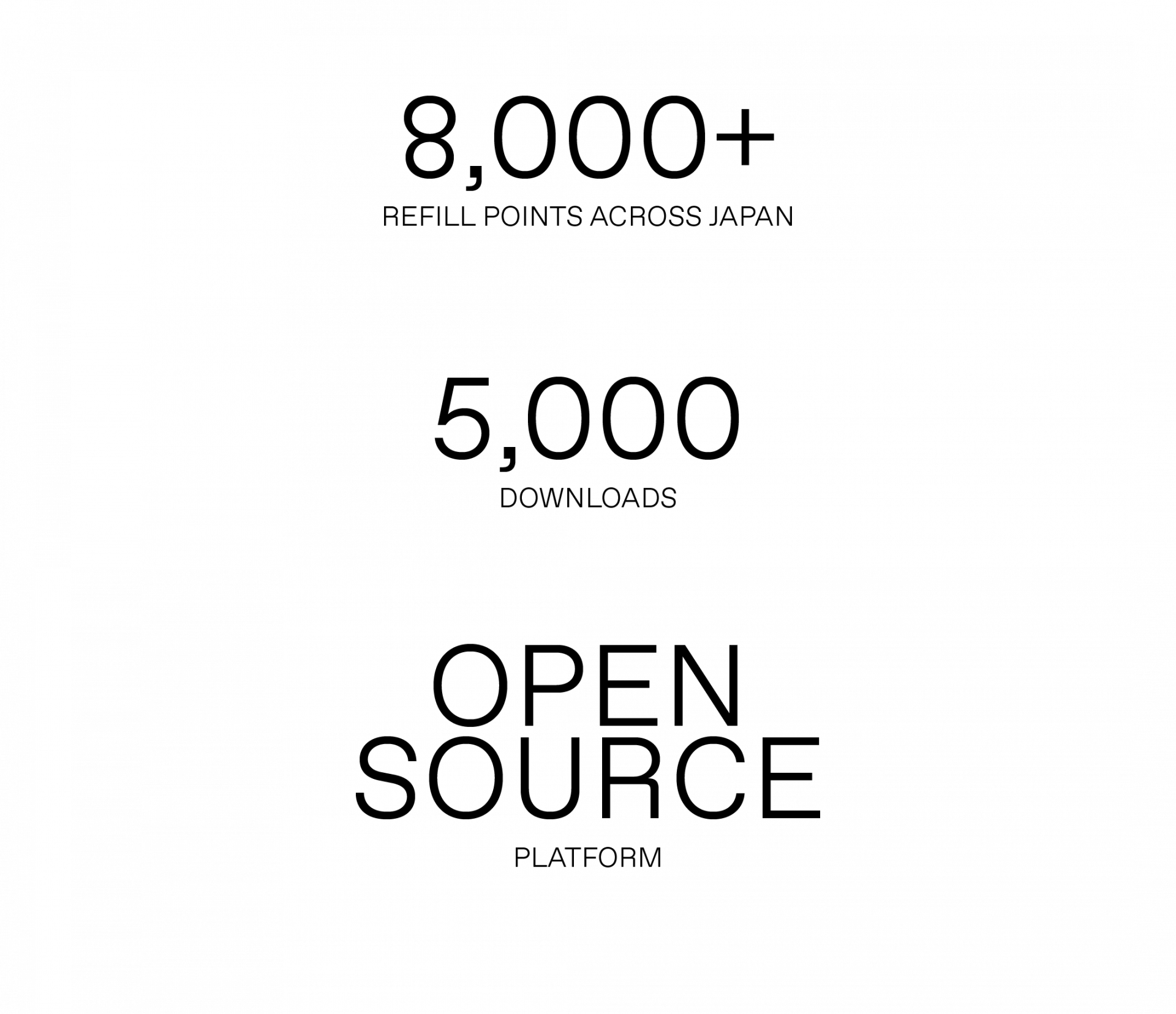

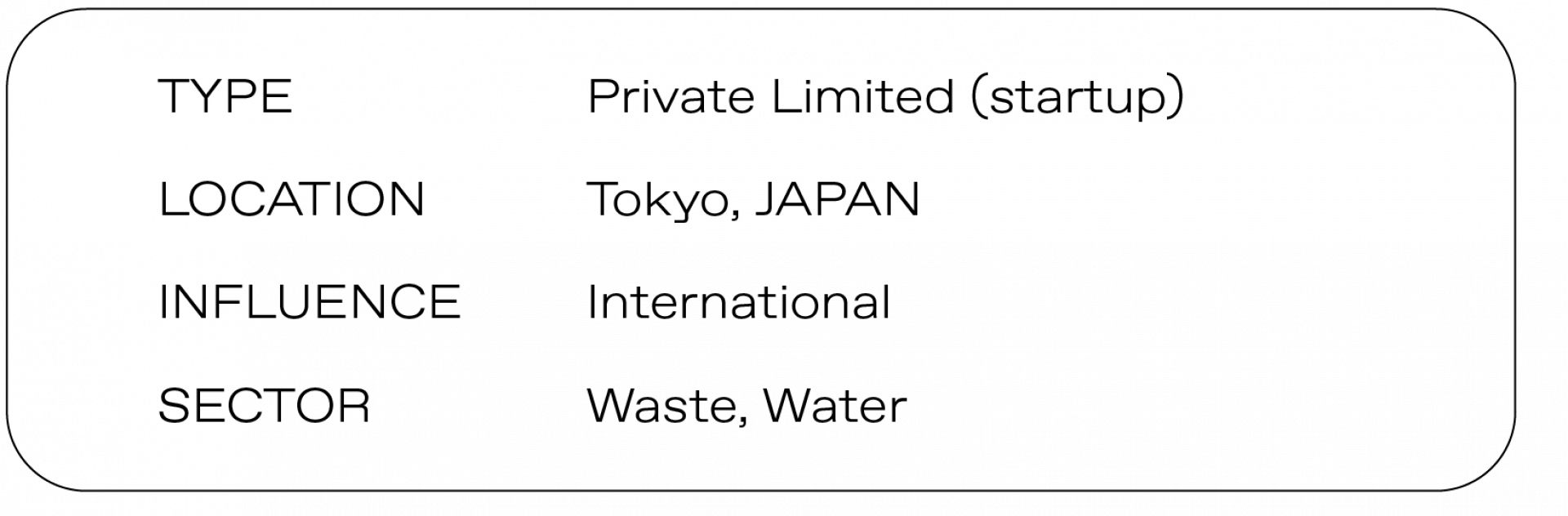

MYMIZU

An open-source platform reducing Japan’s plastic consumption by enabling a decentralised network of free public water access.

Japan is the world’s second-highest user of plastic packaging, consuming enough PET bottles each year to wrap the globe a hundred times over. But the founders of mymizu are trying to change that. Frustrated by the ubiquity of Japan’s 3 million vending machines — and almost non-existent infrastructure for any sustainable alternatives — Robin Lewis started mymizu with a singular belief: if people have access to free water filling stations on the move, they won’t use as many disposable plastic bottles.

As an open-source platform, the app allows individuals and businesses to flag water-refilling stations in public spaces — like water fountains or friendly businesses — and crowdsource a map of drinking water points throughout the country. For users, it represents easy access to free water, but for partner businesses it embodies an opportunity to increase foot traffic, enhance their branding and play their part in making their local areas more sustainable and liveable.

“Companies have the opportunity and duty to lead this charge and it’s not just a risk, it’s a massive opportunity,” Lewis recently said while being interviewed by the Japan Times. “Look at Patagonia, for example, they are one of the most sustainable companies out there, at least in the Japanese scene, and they are doing incredibly well. Companies that are taking the leap are doing phenomenally in many cases.”